How much carbon does ERW remove? Count metal ions in soil, not carbon

Enhanced rock weathering has become one of climate policy’s more beguiling ideas. Spread crushed basalt across farmland, let natural reactions absorb carbon dioxide, and issue credits to companies eager to buy their way toward net zero. Yet a new scientific review suggests that the arithmetic behind this elegant solution may be badly misaligned with reality — and that today’s carbon markets could be tallying the wrong numbers.

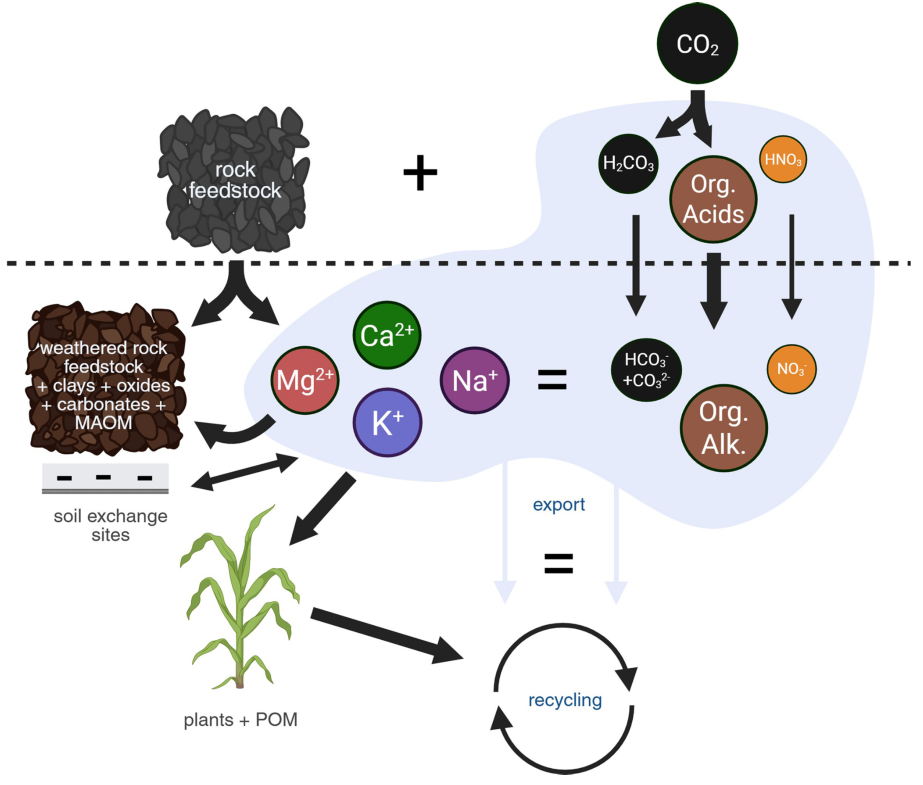

In a paper this month in Biogeosciences, a team led by marine biogeochemist Jelle Bijma of the Alfred Wegener Institute argues that the prevailing method for verifying enhanced weathering removals rests on shaky foundations. Most protocols try to measure how much bicarbonate (CO32-) and dissolved appear in soil water after rock powder is applied. That approach works in laboratories and oceans. On working farmland, the authors say, it borders on fiction.

The problem with counting carbon in soil

An agricultural field is not a sealed container but is a living system. Carbon continuously cycles through roots, microbes, crop residues and fertilizers, much of it escaping back into the atmosphere long before it can be captured in a sampling bottle. Under such conditions, even careful monitoring of carbon in soil or soil water struggles to distinguish newly removed atmospheric carbon from carbon coming from the background churn of biological respiration. The result is an accounting exercise that may look precise on paper while missing much of what actually happens in the ground.

The chemistry itself adds another layer of confusion. In ocean water, tracks carbonate reactions cleanly and serves as a reliable guide to long-term carbon storage. In soils, however, organic acids and dissolved organic compounds interfere with measurment of alkalinity. The widely used method of a sample to measure alkalinity works well for ocean water, but is distorted in soil pore waters because it cannot distinguish between inorganic carbon (carbon from the atmosphere), from organic carbon (carbon originating from biological processes).

A better approach to carbon counting

Rather than pursuing elusive carbon molecules, the authors propose following a different path: the metal released as silicate minerals dissolve. Calcium (Ca2+) and magnesium (Mg2+) cations carry positive charges that must eventually be balanced by negatively-charged carbon-bearing anions (e.g., bicarbonate, HCO3-) somewhere in the system — most often in the ocean, where carbon can remain locked away for thousands of years. By tracking calcium and magnesium in the soil itself, the researchers argue, scientists will be verifying carbon removal using a quantity that is chemically conservative (i.e., not being significantly impacted by biological or chemical processes), and is easier to measure and far less sensitive to biological noise.

The change in perspective leads to a striking conclusion. Much of the weathering product never leaves the field at all. Instead, it binds to clays and organic matter, helping form mineral-associated organic carbon that can hold several times more carbon per unit charge than dissolved bicarbonate. What appears, under conventional methods, to be a delay or loss in inorganic sequestration may in fact be a gain in durable carbon storage within the clay minerals in soil.

None of this is tidy. Ions can linger for years before percolating into groundwater. Some are absorbed by crops, recycled through manure, or flushed into sewage systems before reaching rivers. Clay formation can temporarily suppress carbonate formation even as it builds long-lived carbon-mineral complexes. The system, the authors acknowledge, is intricate and highly dependent on soil type, hydrology and farm practice.

Still, they contend that complexity is not an excuse for flawed bookkeeping. A mass-balance approach based on ion inventories, combined with periodic soil sampling already familiar to farmers, could provide a more credible and less expensive verification system than continuous carbon monitoring in open fields. Conservative correction factors could account for buffering losses and delays without demanding laboratory-grade surveillance across millions of hectares.

Broader implications

The implications extend beyond academic debate. Voluntary carbon markets are beginning to price enhanced weathering credits, and investors are betting that the technique can scale to gigaton levels of carbon credits. If current protocols systematically miscount removals, regulators may face difficult questions about the environmental integrity of this rapidly growing carbon-credit asset class.

The paper’s message is blunt. Organic and inorganic carbon cycles in soils cannot be disentangled, and bicarbonate alone is the wrong unit to count in farmland chemistry. If enhanced rock weathering is to mature into a credible climate tool, the industry may need to rethink what it measures — and accept that in the business of removing carbon, sometimes the clearest signal comes not from carbon itself, but from the quiet movement of metal (calcium and magnesium) ions through the soil.