STRATOS closing in on commercial launch

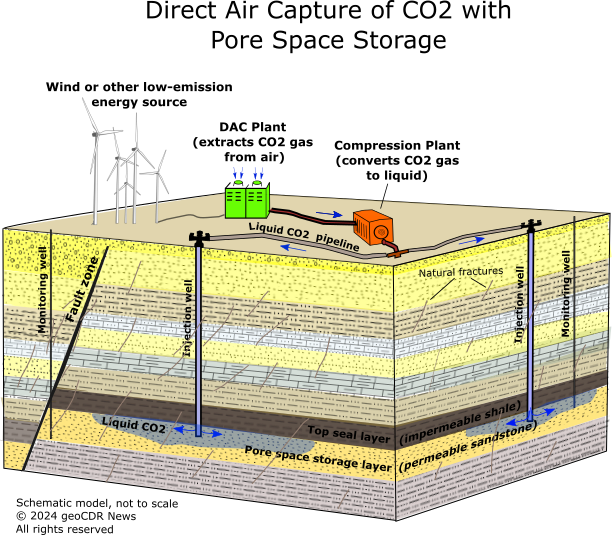

Occidental Petroleum said its STRATOS direct-air-capture plant in West Texas has moved from construction into commissioning, testing early systems as it works toward a commercial launch of a facility designed to remove up to 500,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide a year. Powered by solar energy and backed by newly approved EPA injection permits, the project is positioned to become one of the world’s largest operating carbon-removal plants once fully scaled. Full article >>

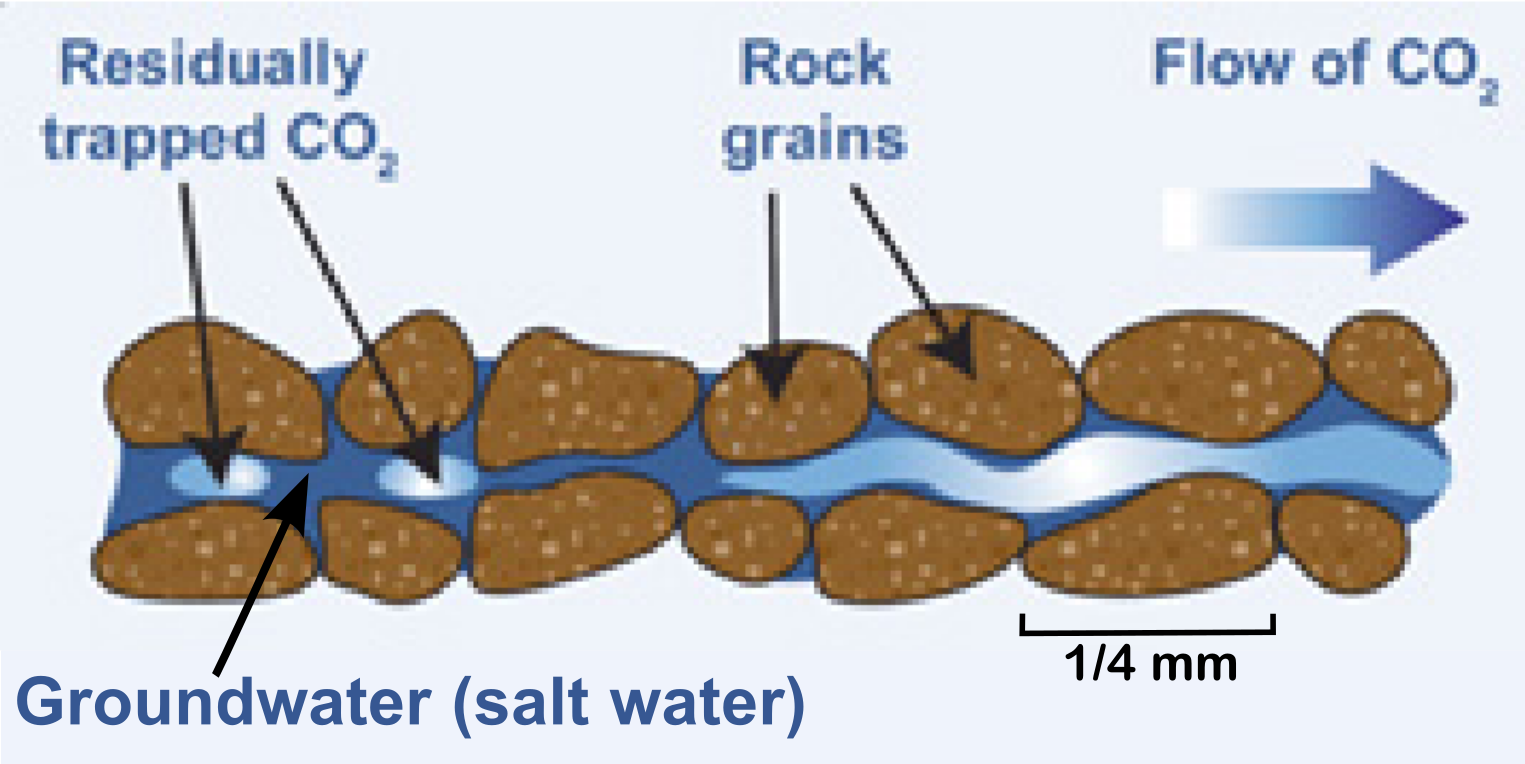

Earth's capacity for storing CO2 underground in pore space may be much less than expected

A new GIS-based analysis suggests Earth’s capacity to store CO2 in underground pore space may be far smaller than long-assumed, falling to roughly 1,460 gigatonnes once environmental, land-use, and drilling constraints are factored in. The finding raises concerns that future generations could face storage shortages unless emissions fall faster or alternative mineralization-based storage options mature. Full article >>

Feasibility study of nuclear-powered DACPS completed

A U.S. Department of Energy–funded study has concluded that waste heat from the Farley nuclear power plant in Alabama could power a pilot-scale direct air capture facility, achieving an estimated 92.5% net carbon-removal efficiency. While technically feasible, such a project would face major economic hurdles, with analysts noting that high costs, low capture volumes, and dependence on incentives such as 45Q would make financing difficult. Full article >>

Direct air capture will supply some of the CO2 in the first industrial-scale carbon capture and storage project in the southeastern Mediterranean

EnEarth plans to make direct air capture a component of Greece’s first industrial-scale carbon-capture and storage project, sending CO2 from both industrial emitters and a new DAC plant to the depleted Prinos oil field for permanent geological storage. Backed by €150 million in government support and aiming for operations as early as 2025–26, the project would create a major Mediterranean CO2-storage hub and deploy RepAir’s electrochemical DAC technology at scale. Full article >>

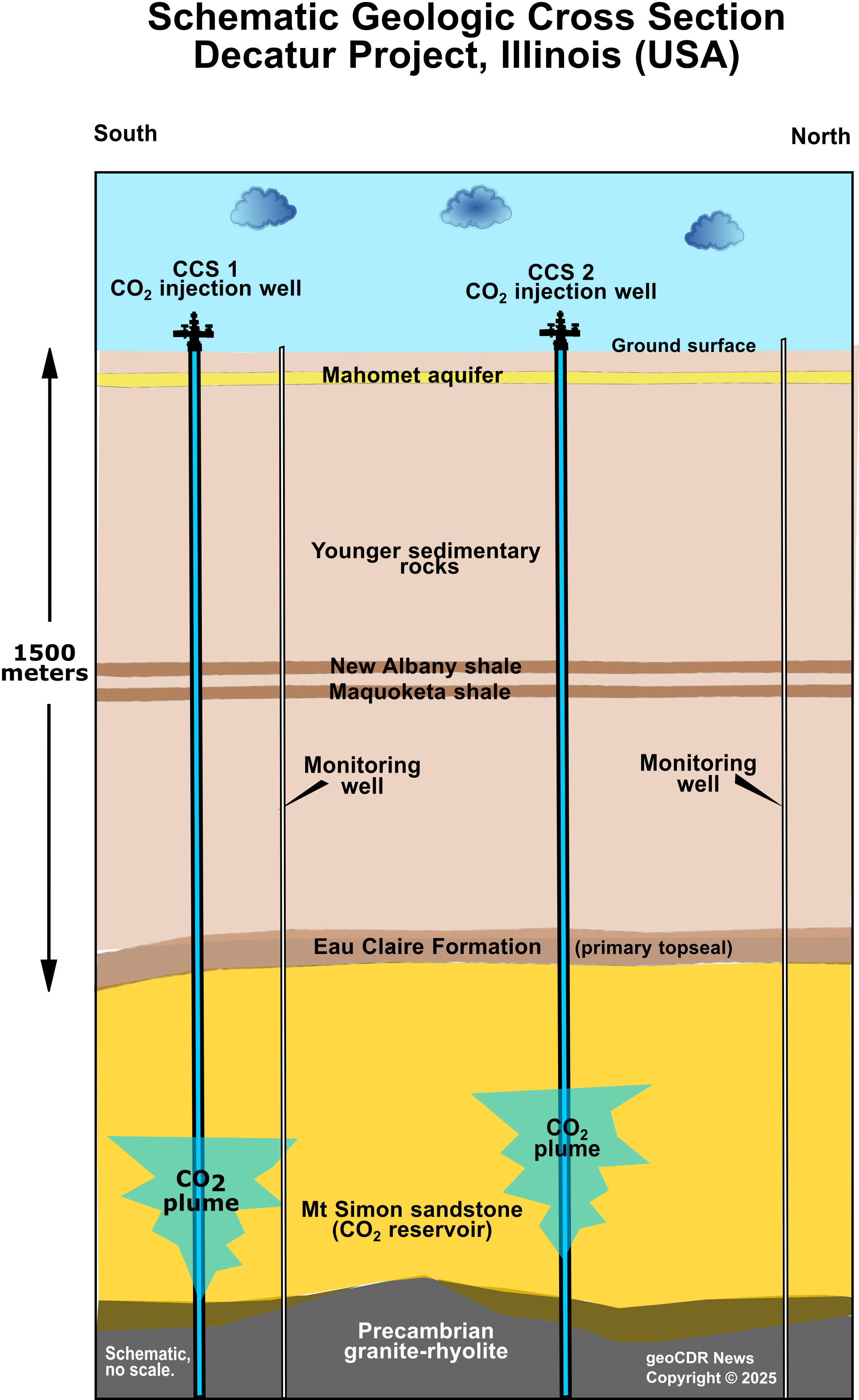

Equipment malfunctions at CCS sites in Norway and U.S. underscore need for robust monitoring, reporting, and verification in carbon storage underground

Equipment failures at major CCS projects in Norway and the United States—one leading to years of over-reported CO2 injection at Equinor’s Sleipner site and another causing a leak into an unintended formation at ADM’s Decatur facility—are raising fresh concerns about the reliability of underground carbon storage. The incidents highlight the need for stricter monitoring, transparent reporting, and stronger regulatory oversight as CO2 storage expands to support net-zero goals. Full article >>

CarbonCapture Inc. shifts strategy, plans DACPS project in Louisiana carbon removal hub

CarbonCapture Inc. has shelved its ambitious Wyoming DAC project after competition from data centers and other industries made it nearly impossible to secure the clean power needed for large-scale air-capture operations. The company is now pivoting to Louisiana, where it has won a federal contract to study a 200,000-ton DAC-with-storage project that could anchor a new Gulf Coast carbon-removal hub. Full article >>

STRATOS, the world’s largest DACPS plant is under construction in West Texas (USA)

Occidental Petroleum is building STRATOS, a $1.3 billion direct air capture plant in West Texas that is slated to become the world’s largest facility of its kind, designed to remove up to 500,000 metric tons of CO2 per year and store it underground in the Permian Basin. Backed by partners including BlackRock and buyers such as Microsoft and Airbus, the project underscores both the surging corporate demand for high-quality carbon-removal credits and the growing debate over whether DAC can scale quickly enough to meaningfully cut emissions. Full article >>